Danielle V. Minson — Raising the Bar

Civil Rights is Our Battle Too: The 1961 Freedom Rides — by Harriet Englander

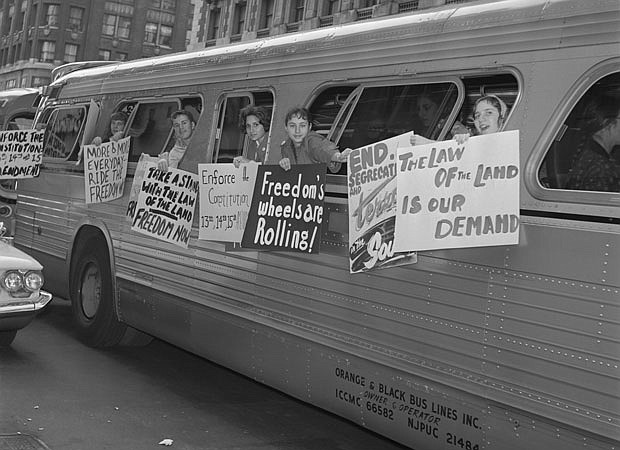

MY FREEDOM RIDE, 1961

CORE’s Route 40 Project

By Harriet Englander

In the early 1960s, as many African countries gained their independence from colonial rule, they sent their diplomats to the United States. These African dignitaries soon complained that when they drove from their embassies in Washington, D.C. to the United Nations in New York City along the favored route, Route 40, they were turned away from restaurants and gas stations despite the diplomatic license plates on their cars.

The Kennedy administration was embarrassed by the situation and began pressuring restaurants and gas stations along Route 40 to serve African diplomats. Half the restaurants, approximately forty-seven along the route, agreed. However, the administration became more embarrassed when black Americans complained that it was unjust for restaurants to serve African diplomats but not black American-born citizens. In fact, black college students from nearby colleges dressed in African garb, pretended to be diplomats, and were served.

The federal government then began pressuring the Maryland legislature to desegregate Route 40 altogether. When the legislature resisted, CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, claimed a partial victory for the 47 restaurants, and intensified their campaign, recruiting volunteers for sit-ins along the Route from Baltimore to Wilmington.

Northern student groups from many universities, including New York University, responded with volunteers. Bob Adelman, a friend of mine, was serving as the photographer for CORE. He invited me to join a freedom ride to a college town south of Cambridge, Maryland, and I accepted.

Our bus left from the NYU student center between four and five in the morning. It was like being on a ski trip to Whiteface Mountain in the Adirondacks. We talked, we tried to sleep, and we sang. When the bus stopped five hours later at our destination, a black church, our bus driver, watching us get off the bus, looked more scared for us than we were for ourselves. We weren’t afraid because the brutal hosings and beatings hadn’t begun, possibly because Bobby Kennedy was Attorney General. I believed he had scared the racists for that moment. And I didn’t think we had gone very far south, where I thought the brutal confrontations would be.

The organizers of this sit-in, college students, many from Howard University, welcomed us into a spacious recreation hall. “Hi,” “Hello,” “Welcome,” “Thanks for coming.” They were a little stiff. So were we. It was awkward but we were enthusiastic. We got our assignments and were introduced to our partners. Most of the group was going to restaurants that had not desegregated, and to those that had agreed to desegregate to make sure they really were.

I was introduced to my partner, Wayne, and we got our instructions. We were going to a bowling alley to desegregate it.

Wayne did not look thrilled with the assignment, nor with having me as his partner. At least, that’s what I felt. We had strict instructions not to resist the law. Wherever we went, we had to walk away peacefully, even if we failed at our goal. They didn’t want a Northern white girl in jail. Wayne was from Baltimore. He was still in college. I had graduated from college four years before.

When we left the church, and began walking, Wayne focused on his map. Most of the conversation was about directions: “We turn here”…. “Wait for the light.” It was a long walk on a cool fall day and no one bothered us or bothered to look at us, I thought. Wayne was serious, good looking, and dressed in business attire: a white shirt, tie, light jacket, and slacks.

We walked on a wide boulevard, tree-lined and quiet with houses set back from the road. We turned onto a side street after nearly an hour of walking and then I saw the sign for the bowling alley. I was a little worried because the one time I’d gone bowling before, I was with my older bothers and I didn’t have the strength to pick up the ball.

Wayne held the door for me and we walked in as far as the entrance.

“You are not welcome here,” said a burly man looking sharply at Wayne. The man was sitting on a high stool behind a counter. Past this dark corridor, I could see the bowling alleys.

“Why aren’t I welcome?”asked my partner.

“Because Neegruz can’t come in here. There’s a law against it.”

I stood a little behind Wayne with my back on the door.

Wayne asked, “Would you please read that law to me.”

I wasn’t ready for Wayne’s reply to this bully. I was honored to be standing almost next to him, only a little behind him. Now I began to see the seriousness of what we were doing. For one thing, we were confronting a bigot in a bowling alley.

“Okay,” said the guy on the stool. “I’ll call the state police.”

He came back a few minutes later. “He’s coming. He’s gonna read you the law.”

We stood at the door for about ten minutes. I was aware of a few glares, and some stares from the bowlers, but mostly they pretended we weren’t there. The state trooper who walked in could’ve been in the movies. He was tall, blond, and skinny, working busily to pull out a piece of paper from his shirt pocket and unfold it. Then he read us the Jim Crow law.

As the trooper read Maryland’s racist law, some bowlers stopped and watched and listened. I realized I had never understood that these segregationist laws required the separation of whites from “persons of color” in any and every situation. The law applied to schools, transportation, cemeteries, and restaurants. Any business owner had the right to legally refuse service to people because of the color of their skin. I was in shock. I had never understood that the law encompassed every activity and all places. It was a vile piece of writing but as my stomach churned, I had to force my mind from gasping at every grammatical error. It was a wretched, stupid law and the least of it was that it was ungrammatically written.

When the trooper finished, he pushed the paper into his pocket and left without looking at us or at the man who had requested this presentation.

We had to follow our instructions. We turned to the door and walked out after him.

“Well, what are we going to do now?” Wayne asked, a little down. It had begun to rain. I said I didn’t know. I felt so guilty. Because of me he hadn’t gone to jail.

“Okay. Let’s picket,” he said.

I was still reeling from my first introduction to the all-encompassing restrictions of the Jim Crow law in Maryland. I was feeling a little wobbly, a little disgusted with myself for not understanding its scope before having it read to me. I had no idea what Wayne meant about picketing since we had no placards, no signs.

“Okay,” I said.

We began walking in a circle in front of the bowling alley. Drivers stuck their heads out of their windows to stare at us. Pedestrians gasped. The state trooper sat in his car. The rain came down on us. The pavement was covered in puddles. I was wearing a soaking wet scarf and a spring coat from Ireland, nicely woven. My partner had no coat and no hat. We walked in this circle silently for about twenty minutes until the trooper got out of his car and suggested we leave. So we left.

On our way to the center of town, we admitted to one another that we were starving. Neither of us had brought a snack nor had either of us eaten breakfast. We decided to try our luck at the lunch counters along the boulevard.

“Girlie, what can I do for you?” asked a man behind an open restaurant window before he knew I was not alone. He reminded me of the guys who stood behind Nathan’s hot dog stand in Coney Island in Brooklyn.

“We would like to get a sandwich,” I said, shoulder to shoulder with Wayne.

“Oh, I can’t,” he said.

“You know you can’t,” said another.

“I’m sorry,” said a third. A fourth said the same before turning away.

Dispirited, we walked humbly into a grocery store and asked the cashier if we could buy some bread and baloney. She may have been the owner because she smiled softly and told us, “Go ahead.” We selected a package of baloney, half a loaf of white bread, and some mayonnaise. We stood in the back of the store and broke open the packages, put the meat between two pieces of bread, and pushed the mayonnaise out of a tube. We ate our sandwiches standing in a back corner of the store.

Feeling less hungry, we walked along the thoroughfare, and as we got close to the church, we saw that the street was crowded, with blacks and whites on opposite sides. People were shouting and throwing rocks and bottles across the boulevard at one another. I couldn’t help feeling that our busload of white interlopers had turned these quiet people into a raging mob. It was such a sharp contrast from the walk we had taken in the morning. No one ever told me why they were fighting and if my hunch was right.

We were not disturbed by the mob as we walked quickly to the church, but both of us were totally drenched. My light brown hair dripped along my neck in clammy strings and my bangs were down over my eyes. As we walked into the church, everyone was singing “We Shall Overcome.” Wayne and I shook hands and smiled wholeheartedly as we said goodbye. I knew he was pleased he had made those racists read us those rules of hatred. He headed to meet his group and I headed for the hot dogs the ladies were handing out in the back of the hall. I had two hot dogs on buns and a cup of coffee, fortifying myself for the five-hour trip home.

Sitting on the bus, I thought about the young people who had been singing “We Shall Overcome” who weren’t getting on a bus to New York. It wasn’t going to be a one-time event for them. These local freedom riders from Baltimore and the college towns nearby would be staying for a long fight.

I learned a lot that day, and when I wrote about it, I thought it would be a period piece from the sixties where so much progress would follow. I didn’t realize it would be two steps forward and three steps back.

I never imagined that I would be rewriting this report fifty-nine years later in my 85th year because, despite some progress and some hope, the bloody conflict of the sixties had become a never-ending fight.

Research Note: data base.swarthmore.edu/content/cores-route-40-project-maryland campaign-desegregation-and us-civil-rights-1961.

Global Nonviolent Action Database CORE’s Route 40 Project: Maryland campaign for desegregation and U.S. Civil Rights, 1961